Hands-On: Snapdragon Dev Kit for Windows

- Paul Thurrott

- Dec 22, 2024

-

7

Thanks to its strange, short history, the Qualcomm Snapdragon Dev Kit for Windows (2024) is a curiosity and a one-off, never to be repeated. I wrote previously about the issues I had recovering the PC when it arrived, and I think what I experienced hints at why Qualcomm pulled the plug. This thing is … quirky and, in some critical ways, non-standard. As I write this, I still haven’t successfully booted the Dev Kit with a USB flash drive, and the lack of documentation is disconcerting.

Reviewing the Dev Kit doesn’t make a lot of sense for all the reasons, including the most obvious, that you can’t even buy the damn thing now. But I am of course fascinated by it, and if it makes sense to do so—ideally, I could reliably recover the thing from outside of Windows, for starters—I’d like to use it daily. But first thing first. Here’s a high-level overview of this interesting PC. I think it hints at what a coming generation of Snapdragon X-based desktop PCs will offer.

Windows Intelligence In Your Inbox

Sign up for our new free newsletter to get three time-saving tips each Friday — and get free copies of Paul Thurrott's Windows 11 and Windows 10 Field Guides (normally $9.99) as a special welcome gift!

"*" indicates required fields

Existential questions

If you ignore that it’s a small form factor (SFF) desktop PC, the Dev Kit is quite similar to the Snapdragon X-based Copilot+ PC laptops I’ve fallen in love with this past year. Which raises a question.

Is it a Copilot+ PC?

Yes. Yes, it is. At first, I wasn’t sure. But the basic specs—a processor with a compatible NPU, RAM, and storage—are all there. Windows 11 reports that Windows Hello ESS is enabled, even though there’s no compatible fingerprint reader or webcam. (Leaving PIN, of course.) And it includes all the unique Copilot+ PC features, like Cocreator in Paint, Restyle image and Background blur, remove, and replace in Photos, and so on. So yes, it is a Copilot+ PC.

What’s missing, however, is a Copilot key or button. The recently announced ASUS NUC 14 Pro AI has one (in button form), but as I wrote at the time, it’s not clear if that’s a real requirement for desktop Copilot+ PCs or if ASUS was just trying their hardest. It doesn’t matter, I guess. The Dev Box is unique, and I’m sure including those AI experiences was on the list of things Microsoft and Qualcomm wanted the developers this thing targeted to experience.

Specifications

Ignoring the product design yet again, the Dev Kit specifications—internally, and including its expansion capabilities—are likewise quite familiar. With one obvious exception: The processor. Which is perhaps the most curious thing about this curiosity.

At the time of the announcement, Qualcomm described the Dev Kit’s processor as “a special, accelerated Developer Edition of the Snapdragon X Elite processor.” Since then, we’ve come to understand this to be a Snapdragon X Elite X1E-00-1DE, the rare highest-end version of this processor family. It’s nearly identical to the X Elite X1E-84-100, with the same 12 cores, 42 MB of cache, 3.8 GHz multi-core frequency, 4.6 TFLOPS Adreno GPU, and 45 TOPS NPU. The only thing that differentiates the two, and then just barely, is the X1E-00-1DE’s 4.3 GHz dual-core boost frequency, vs. 4.2 GHz for the X1E-84-100.

My guess is that this is just a coincidence of the manufacturing process, and that the X Elite X1E-00-1DE is really just a X1E-84-100 that randomly exceeded a certain quality level. Indeed, the entire Snapdragon X processor family, including the lower-end X Plus models, feels like an experiment testing the limits of processor binning. Many of the chips are only subtly different from the others. But this may be the most subtle.

Getting past that, the Dev Box was offered in just a single configuration with 32 GB of LPDDR5x RAM, and 512 GB of NVMe SSD storage. This is just a slice in time, but this is what I consider to be the current sweet spot for a laptop, though I understand others might need more storage. (And others would be OK with 16 GB of RAM, which I consider the minimum heading into 2025.) But whatever. This is a reasonable configuration for app development and testing.

Connectivity includes Wi-Fi 7 and Bluetooth 5.4, currently as modern as there is. I’ve had no issues with either.

Expansion is modern and it mirrors what we’ve seen on most Snapdragon X-based Copilot+ PCs, with a few differences tied to the form factor.

On the front of the unit, there is a single Thunderbolt 4/USB Type-C port and, hidden behind a ridiculous hard plastic door, a microSD card slot.

On the rear, there’s a full-sized Ethernet port, two USB 3.2 Type-A ports (which I assume are 5 Gbps and designed mostly for legacy peripherals like keyboards), two Thunderbolt 4/USB Type-C ports, and a combo mic/headphone jack. Plus the power port (on the far left).

The right side of the PC isn’t used, but the left side has a large vent for heat dissipation.

And it’s frequently needed: Where I have rarely noticed the fans found in Copilot+ PC laptops—never, really, aside from running video encoding tests and other tasks specifically designed to hammer the system—the fan in this PC is a near-constant companion. It comes on seemingly randomly, reminding me of the disk indexing drama of two decades ago that freaked out people who didn’t understand what was happening—and it comes on and stays on in certain circumstances. (See below.) It’s loud and then it’s not loud, and then it’s loud again and then it’s off for a while. It’s … OK. Not great. But not a killer.

Unboxing

There’s not much going on here. The Dev Kit arrived in a basic box with two tiny pamphlet-like papers that are mostly irrelevant now since the QR codes they contain no longer resolve to anything, let alone anything useful. The box includes the PC, of course, plus its large power supply (with proprietary barrel connector) and the USB-C to HDMI dongle that many believe is tied to the reasons behind this PC’s delays and then cancelation. (Qualcomm originally advertised the Dev Kit as having an HDMI-out port, and there is an empty space on the daughter card that also includes the Ethernet port for that part.)

I would prefer a built-in HDMI-out port: It’s possible I’d have an easier time figuring out which keys do what when you boot the PC—documentation here is so key—with a “normal” display over HDMI. USB-C displays sleep/wake on a hair trigger, I assume for power reasons, and it’s not clear that I’m seeing everything this PC outputs when it boots with a USB-C display.

Anyway, despite the suspected weirdness, almost everything works as expected for the most part. The one obvious exception is tied to the boot process that I would really like to fully understand.

When you turn on or reboot the PC, it often goes through some silent machinations that take many, many seconds, and it seems to do one or two soft reboots during this, though not every time. There’s no rhyme or reason to this. The power button on the front of the PC can flash white, green, red, or blue, and occasionally, it does all three. Fun!

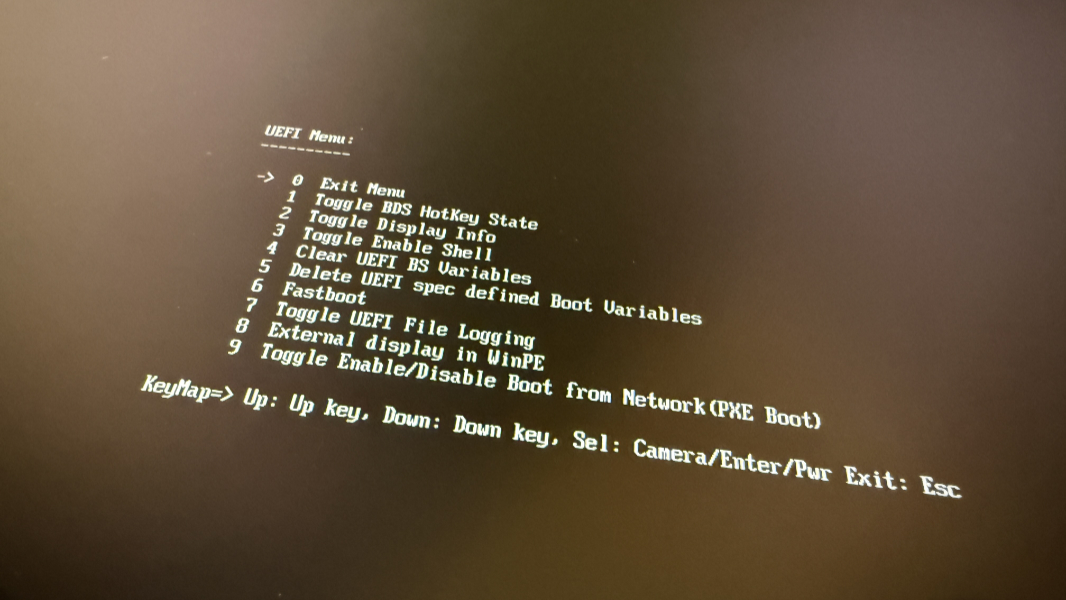

I did figure out how to get into the firmware’s BDS menu—it doesn’t appear to have a traditional PC-style firmware interface, and I assume this thing is phone-based—as noted previously. But this is so unfamiliar, and so different from what we see on normal PCs, and I know I’m missing things. I’ll keep working on it, but at some point, it’s just a waste of time. Snapdragon X-based laptops like my Surface Laptop 7 work normally in this regard. So this may just be a one-off.

Initial setup

Here, too, there are no surprises. The Dev Box displays the familiar Windows 11 Out of Box Experience (OOBE)—it comes with Windows 11 Home, not Pro—and it included the lengthier feature update installation phase I first started seeing this past summer that’s new to 24H2. And then it boots into the desktop normally. Nothing odd there.

There were a few curious configurations, however.

The Power Mode was set to Best Performance for some reason, and not Balanced as is typical. As noted below, it’s not clear what these modes even mean now on Arm—there’s no discernible performance difference in day-to-day use or under load—but I switched it to Balanced.

Even more oddly, the screen and sleep timeouts were both set to Never. I usually extend the defaults, but in this case, I was sort of going in the opposite direction. I also changed what happens when you press the power button: It was set to Do Nothing, and I changed that to Sleep.

I wrote about the bizarre way the disk is laid out in my previous article. If I can ever boot from USB, I will clean install the OS and fix that. Not sure what’s going on there.

Most configurations are as expected. It auto-enabled OneDrive Folder Backup, for example, in keeping with the default behavior for Windows 11 Home.

Video encoding test

I’m no fan of benchmarks, but I felt like the unique processor in the Dev Box required something semi-formal. Yes, the X Elite X1E-00-1DE in the Dev Box is only subtly different from the X1E-84-100. But most Copilot+ PCs don’t include either of those processors. Instead, most come with an X Elite X1E-80-100 processor (or, now, an X Plus processor of whatever variant).

The solution was obvious enough. This past summer, I did some video encoding tests to see how the first few Snapdragon X-based Copilot+ PCs compared to the MacBook Air M3 and a high-end laptop with discrete graphics. I also wanted to test a Qualcomm claim that the Snapdragon X chips didn’t throttle performance as badly as do x86 chips when on battery power.

My tests were unscientific enough to not prove much of anything, but I guess my key takeaway was that the Snapdragon X held its own. And the Dev Box doesn’t have a battery, of course. But I was curious. So I performed the same video encoding test—in which I take the 4K version of the Tears of Steel video and use (the native Arm version of) Handbrake to encode it to Full HD using its Fast 1080p 30 preset.

The results surprised me enough that I re-ran this test multiple times. Put simply, it encoded the video in just under 2 minutes and 40 seconds, no matter which power management setting I chose. Balanced, Best performance, and Best efficiency all worked identically, and the fans roared to life and stayed on for the duration of this encoding. I suspect this is as loud as this kind/size fan can be.

As surprising, that time frame was so dramatically lower than the results I saw over the summer that they’re not comparable. Clearly, something was off.

So there was only one thing to do: Re-run the tests. Not on multiple PCs, I have a life to live. But I downloaded the video and Handbrake to my Surface Laptop 7, left it on battery (and with the default Recommended power management mode), and encoded the video. It took an average of 5:49 over two runs. On power, it encoded the video in just over 4 minutes.

There could be other factors that impact the score here. But I’m surprised the Dev Box is that much faster.

Looking ahead

Over the holiday break, I’ll see whether it makes sense to use the Snapdragon Dev Kit for Windows as my main podcasting PC. I’m going to crack open the box and poke around inside. And I will continue working on recovery and boot from USB, I got some good leads from readers and feel like both are surmountable issues. But let me know if you have any questions.